Imagine

a world where the sky was green. Not because you were on a different planet but

because you didn’t know the word ‘blue’…

This

may seem like the stuff of science fiction but empirical evidence

over the years is now suggesting that our words might indeed be shaping our

thoughts and perceptions.

Benjamin

Lee Whorf, a linguist and a fire prevention engineer, was one of the

pioneers to put forward this idea of linguistic relativity with Edward

Sapir - his mentor at Yale. Their fundamental idea was that linguistic

categories influence perception and cognition or putting it simply - our

language and our words influence our thoughts and our perceptions.

Yes. You

read it right.

Our

words influence our thoughts and our perceptions. Not just the other way

around.

Sapir

and Whorf's idea of linguistic relativity was explicitly drawn on Einstein's

principle of general relativity such that the grammatical and semantic

categories of a specific language provide a frame of reference through which

the observations are made. They were deeply influenced by the ideas of

Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose view was that natural language

potentially obscures, rather than facilitates, the mind's ability to perceive

and describe the world as it really is. In the mid-twentieth century, this

argument built the case for the extensive use of formal logic, to question the

very fundamentals of logic and mathematics and to arrive at a set of axioms

based on rigorous thought and didactic reasoning. Whorf built on the

ideas of Nietzsche and Wittgenstein and developed the theory of linguistic

relativity but it was based on little empirical evidence and thus fell out of

with the intellectual community within a decade of his death. In one oft quoted passage, Whorf

writes:

"We

dissect nature along lines laid down by our native language. The categories and

types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find there because

they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is presented

in a kaleidoscope flux of impressions which has to be organized by our

minds—and this means largely by the linguistic systems of our minds. We cut

nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do,

largely because we are parties to an agreement to organize it in this way—an

agreement that holds throughout our speech community and is codified in the

patterns of our language. The agreement is of course, an implicit and unstated

one, but its terms are absolutely obligatory; we cannot talk at all except by subscribing

to the organization and classification of data that the agreement decrees. We

are thus introduced to a new principle of relativity, which holds that all

observers are not led by the same physical evidence to the same picture of the

universe, unless their linguistic backgrounds are similar, or can in some way

be calibrated."

But can this really be true? Can our

language determine our perception of the universe?

Apparently,

it can. And, here is some of the evidence for it that has compelled me to make

that existential flip in my thinking and perception.

1) Blue

or Green - the brain sees it only when it 'knows' it

In

a classical debate, cognitive scientists have been trying to

establish the relation between language and perception. At one end of this

debate is the strong -form Whorfian-theory that says that our perception of the

world is shaped by the semantic categories of our native language and that

these categories vary widely across languages. At the other end of the debate

spectrum, is the universalist stance which claims instead that there is a

universal repertoire of human thought and perception which leaves its imprint

on all the languages of the world. Over the years, evidence has swung back

and forth but empirical evidence from the domain of color and color-perception

were some of the first and most comprehensive to weigh in on this rather

fundamental question.

The

effect of language on thought and perception was first tested with color

perception in a 2006 study by Gilbert et al. Their study attempted to

probe the perceptual discrimination of colors that straddled the boundary of

blue and green - a boundary that exists in the English language but is absent in

many others. The question was: does having a label for a color made a difference

in how we see it?

As

part of the experiment, English (American) speaking participants were

presented with a central fixation cross with a ring of colored squares tiled

around it. All the squares in the ring were of the same color except for the

target. The participants were required to identify the differently colored

square and indicate its location on the left vs. right side of the ring by

pressing a button with the corresponding hand. The test was designed in such a

way that the target color had either the same name as the color of the other

squares (eg. green against the background of a different green) or a different

name (eg. green against a background of blue) i.e. belonged to the same

category or to a different category.

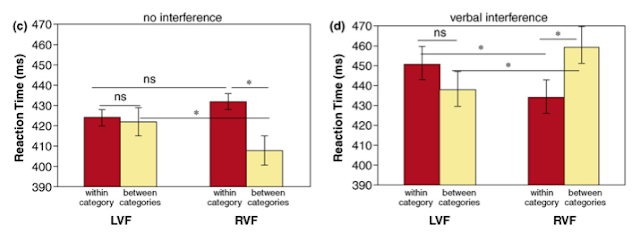

Termed

as Categorical perception (CP), this test was designed to see if having a

different word/name for a color improved our ability to perceive it especially

when the stimuli lie at the edge of a boundary.

Instead

of a simple yes or no answer the experiment yielded a rather interesting

pattern: The subjects were better able to identify cross-category targets faster

than same-category targets but only when presented in their right visual field,

thus suggesting that Whorf's hypothesis might have been right after all; atleast

half of it.

Interestingly

our language faculties are localized in our left hemisphere and the brain

functions contra-laterally (left side of the brain controlling the right visual

field). To test the effect of language, a parallel task requiring the use of

verbal resources was added to the test and interestingly the effect on

categorical perception by the left hemisphere (in the right visual field/RVF)

was lost and in fact, was reversed. They also found that such a reversal was

not seen when a non-verbal task of similar difficulty was added, thus

suggesting that this lateralization effect was because of our

language indeed.

As

one would expect, split brain patients whose left and right hemispheres are

unable to talk to each other lost any trace of CP bias in the left visual

field/LVF.

Interestingly

at the time, a separate study by the same group expanded this paradigm to the

use of non-color stimuli, namely silhouettes of dogs and cats thus extending

the effect of our words on the way we think and perceive the world.

But

then what happens in children who are as yet uncorrupted by language? Do

children who cannot yet talk, see and think differently from children who

can?

This

is a rather interesting question and was addressed in a study by Franklin et al

in 2008 as they first compared infant and adult performance on a visual search

task much like that used earlier by Gilbert's 2006 study. As seen previously,

adults showed dominant CP in their right visual field influenced by the language

center in the left hemisphere. The pre-linguistic infants however showed

no such CP bias in the Right visual field (RVF) and instead exhibited a clear

CP in the left visual field (LVF). Thus, it seemed that as the children grew up

and acquired language, there was a migration in their perception of categories

from the RH/LVF (as infants) to the LH/RVF as adults (with language).

Instead

of comparing two very different groups - the infants and the adults, Franklin

et al, next compared toddlers (2-5 yr old) in two groups: the learners and the

namers. While the namers already had acquired their color terms, the learners

were still finding their way around the color spectrum. Interestingly, the

learners patterned colors like the infants while the namers showed CP like the

adults. This strongly suggested that learning the color terms causes a shift in

our categorization of color perception from the right hemisphere to the

left.

What

seemed like green to start with suddenly starts looking different once we learn

the word blue.

When

investigated further, these differences in color perception were further

mimicked at the deeper level of electrical activity in the brain. Functional

MRI studies have found that discriminating colors of different lexical

categories (vs. the same category) elicited a faster and stronger response in

the language regions of the left hemisphere especially when the

colors were presented in the right visual field. Based on these studies over

the past decade, it thus seems uncontroversial now, that once language is

learned, the language labels replace any existing categories and shape our

perceptual discrimination (especially in the left hemisphere/ right visual

field).

2)

Mapping our space-time paradigm - one word at a time

For

a long time in the past, the impact of language on human thought has remained

an intriguing question in the realm of psychology, philosophy and linguistics.

Very little was done to empirically test any of these claims. However, over the

past decade or so, researchers like Lera Boroditsky - a psychologist and

neuroscientist at Stanford, have dared to jump in and get their hands

dirty in trying to arrive at more definitive answers. Research in Dr.

Borodistky's labs at Stanford and MIT is focused on trying to test the

hypothesis that language does shape our thoughts, above and beyond our

abilities to see color or shape. They have collected data from around the

world: from China, Greece, Chile, Indonesia, Russia and Aboriginal Australia

and have found that people who speak different languages do indeed think

differently.

Given

some thought, this effect of language is rather evident because, after

all, different languages tend to provide different levels of information -

gender of the subject/object, tense, verb information etc. While some languages

like Russian alter the verb to indicate the tense and the gender, some others

like Turkish would also indicate how the information was acquired. Some other

Romance languages like Spanish and french, also ascribe gender to common nouns

- thus making a table masculine or feminine. In fact, some Australian

Aboriginal languages have upto sixteen genders that include classes of hunting

weapons, canines, things that are shiny, etc.

Since

languages communicate different information in different forms, it is also

conceivable that the speakers might end up attending to, partitioning and

remembering their experiences differently by virtue of their different

languages? Questions like these have been addressed by the work done by Dr.

Lera's group and others and have brought us farther along this line of

questioning.

Consider

the following examples.

In

northern Australia lies Pormpuraaw - a small aboriginal community on the

western edge of Cape York, where the locals - Kuuk Thaayorre, have a rather

interesting approach to space. Unlike us, english speakers, who define space

relative to an observer by the use of words like right, left, front, back etc,

the Kuuk Thayorre, like many other Aboriginal groups use the cardinal direction

terms - North, South, East and West - to define space. All the time. All space

in this community - from a village to an arm or a leg is specified along

cardinal directions. Not only does it save them from that moment of confusion

we all have, when someone facing us asks us to look right or left, and we

wonder - "my left or your left"; this practice also makes them rather

capable navigators. This constant training of their attention to the

geographical coordinates forces them to pay exquisite attention to their

geographical coordinates - all the time.

But

how does the use of cardinal coordinates really affect thought - not just

navigational ability? And this is where Boroditsky and her group design some

simple experiments to demonstrate that since space is such a fundamental domain

of thought, differences in spatial perception also tend to impinge on our other

more complex and abstract representations too. Surprising as it may seem, it

appears that our representations of things as time, number, musical pitch,

kinship relations, morality, and emotions depend on how we think about space.

For instance, if people are given pictures that are snapshots of a temporal

progression (eg. a man aging or a fruit being eaten) and asked to arrange them

chronologically - one can see some very interesting trends. English speakers

arranged the cards such that time proceeds from left to right. Hebrew speakers

however arranged the cards from right to left (their script progresses from right

to left). The Kuuk Thaayorre on the other hand, lacking such concepts as left

and right followed a completely different trend. Their arrangements were not

random; instead they arranged time from east to west (sunrise to sunset,

perhaps?). So, when facing south, they arranged the cards from left to right;

and when facing north, they went from right to left, and so on.

People's

ideas and representations of time also differed in other ways such that, while

english speakers tend to talk about time using horizontal spatial metaphors

(ahead, behind etc), mandarin speakers use a vertical arrangement for time, in

keeping with their script. When subjects were given a spot for today and

asked to plot yesterday or tomorrow, english speakers nearly always pointed horizontally

while mandarin speakers pointed on the vertical axes. In fact,

Chinese calendars move downwards and across (right to left on the

page) like the written script itself.

In

addition, research also shows a strong effect of language on some of the basic

aspects of time perception. For example, since english speakers prefer to talk

about time or duration in terms of length (short talk vs. long) their

perceptions of time tend to be confused by distance information, such that they

estimate a longer line to have remained on the screen for a longer period of

time, although the two parameters are completely unrelated.

But

these tests are plagued by one critical question - the question of causality.

How do we know that these people of different cultures are perceiving things

differently only because of their language and not because of anything else.

Reason would dictate that if these people learnt a new language, their

perception of the world would change accordingly. And so, in one such study,

English speakers were taught to use size metaphors like in Greek to describe

duration or vertical metaphors like in Mandarin to describe event order.

Remarkably, once the english speakers had learnt to talk about time in these

new ways, their cognitive performance began to resemble that of native Greeks

and Chinese thus establishing a rather conclusive role for language in instructing

how we think.

3)

Word games - when the same 'key' can become heavy or tiny!

The

sub-conscious impact of language also extends from the realm of abstract

concepts like time and space into the more physical.

A

clear case in point is that of grammatical gender as seen in romance languages

like Spanish, German and French where nouns are assigned masculine or

feminine genders. Speakers, in turn have to change pronouns, adjectives, verb

endings, possessives, numerals and so on, depending on the noun's gender.

But

do these subconscious perceptions subsequently bias our opinions of everyday

objects? When tested, it was indeed found to be so. In one study from

Boroditsky's group, the experimenters asked German and Spanish speakers to

describe objects having opposite gender assignment in the two languages to see

how the gender influences perception. When asked to describe a "key"

- a word that is masculine in German and feminine in spanish - the German

speakers used words like "hard", "heavy",

"jagged", "metal", "serrated", "useful"

etc while the spanish speakers were more likely to use words like

"golden", "intricate", "little",

"lovely", "shiny", and "tiny".

Interestingly,

these results emerged even though the testing was done in a third neutral

language like english. The same pattern of results also emerged in entirely

non-linguistic tasks like when subjects had to put images together.

Apparently,

even small flukes of grammar, like the seemingly arbitrary assignment of gender

to a noun, cal dramatically alter our perception of the world.

4)

Honest lies - true testimonies of events that never happened

Honest

lies are factually inaccurate information that we have told with all

honesty because that's what we remember them to be. We have all told them

inadvertently because of when, how and where were asked the question.

Innocent

people have been caught on the wrong side of law while liable culprits and

criminals have sometimes been set free because of this strange malleability of

the human mind. And no one paid much attention to study this phenomenon because

we were all oblivious to how our mind was being tricked and how it was in turn

tricking us, until of course, a psychologist from UC Irvine, Elizabeth Loftus

dived in and highlighted some of these hard-to-swallow facts.

Loftus'

journey began at a social-psychology class when she saw that people could name

a 'yellow bird' faster than a 'bird that's yellow'. Her subsequent search for

interesting puzzles, funds and opportunity, brought her to the US department

of transportation where Loftus began her research into car accidents and the

limitations of eye-witness testimony. She empirically showed that

people's eye-witness testimonies and versions of accidents can vary depending

on the wording of the questions asked of them. She showed people clips of car

accidents and asked them to estimate the speed of cars. People when asked,

"How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?' gave

higher estimates on average than those with whom the verb "hit" was

used. Those who heard the verb 'contacted' in the question gave the lowest

estimates of the speeds again confirming the idea that words and language can

mould and shape our thoughts.

The

effect of words and language on our thinking does not merely extend to how we

judge unknowns like the speed in this instance - they can also mislead us into

fabricating parts of the story. Those asked about cars smashing into one

another were more than twice as likely as others to report seeing broken glass

when asked about the accident a week later, even though there was

none in the video. This clearly suggested that our words and language can

sub-consciously lead us into confabulating 'facts' and contaminating our memory

traces.

After

these dramatic beginnings, Loftus went on to publish several other studies that

showed how memories can be contorted and eye-witness accounts can be tainted.

She has gradually extended her work from the realm of pure academic interest

into having social ramifications and is currently pushing for broader legal

reforms. While the focus of Loftus' studies is on the unreliability of our

memories, her work is also relevant to the effect of language on thinking. As

can be seen from her experiments, the exact phrasing of the question had a

profound effect on what and how people thought and recalled events.

5)

Gender personification, abstraction and art

This

is a rather interesting idea that explores the effect of native languages on an

artists perception of abstract concepts in art such as death, victory,

sin, time etc. When representing such emotions in human forms, how does an

artist decide the gender? Accordingly to Dr. Boroditsky, it appears that in

most such abstract personifications (85% apparently), whether a male or a

female figure is chosen is predicted by the grammatical gender of the word in

the artist's native language. Not too surprising, perhaps, once we make that

Whorfian existential flip.

6)

To see or not to see - It's all in the dictionary!

The

many examples so far establish a critical effect of words on our thinking, on

our ability to categorize and discriminate. But, the effect of language on

perception itself remains. To what extent is the awareness of an object

affected by factors outside of our vision? The traditional view is that

although a number of non-visual factors can affect where and what one attends

to, the very content of what we see is not susceptible to outside influences -

but is determined by physical factors.

However,

a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, does a lot to overthrow this paradigm. Through empirical

evidence, the authors demonstrate a strong effect of language on

perception itself; an effect divorced from any higher level cognitive processing

that one might suspect. They show that auditory linguistic labels can not just

affect what one sees but whether one sees something at all. Their studies show

that an otherwise invisible kangaroo can be boosted into awareness by language,

by using the word for a kangaroo while seeing the stimulus.

This

idea that a "higher-level" process like word recognition or language

can influence a "lower-level" process such as visual perception

presents a challenge to our normal feed-forward modeling of cognition and

perception; where it is assumed that the world is seen for what it is but then

our brains filter out and attend to specific stimuli.

Although

many studies have demonstrated a clear effect of language on post-perception

decision making, an outstanding question in the field is to discriminate the

effect of language on perception vs. perceptual identification. One way to do

this is to keep visual stimulus (object) unchanging while manipulating the

top-down influences that change our perception of the object. This way,

any differences in perception by stimulus-driven processes can be ruled

out.

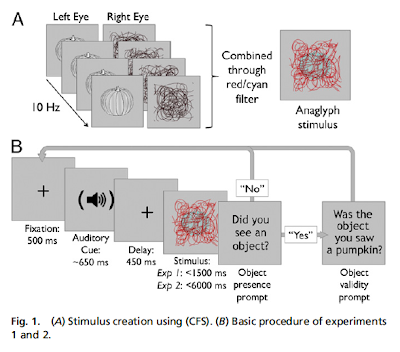

In

this study, the authors investigated whether hearing a language label can

affect our ability to simply detect the presence of an object. In order to

suppress conscious visual awareness along with semantic processing, the authors

use a process called as interocular rivalry i.e. they present different stimuli

to the two eyes, such that the stimuli compete and the same retinal

input can give rise to different conscious percepts. Which of the two

stimuli gain our attention is determined by visual aspects of the stimulus -

contrast, luminosity, size, eccentricity, contour density etc.

Continuous

flash suppression (CFS), a variant of interocular rivalry, is

particularly useful to testing visual awareness and forms the basis of these

experiments. In continuous flash suppression, an object is placed in

interocular competition with high-contrast noise patterns (alternating

really fast at 10 Hz) thus suppressing the real stimulus from awareness for

extended periods of time.

The

authors began by testing if hearing a verbal cue or language label can make an

otherwise invisible object (invisible by CFS) to pop-up and become

visible? They reasoned that if words can change our perception of things,

then hearing a label before seeing a picture (that is

normally invisible due to CFS), should increase

the likelihood of seeing the picture. And indeed, hearing a word

label (like a kangaroo) before the simple detection task increased performance

or increased the ability to detect the "kangaroo". Further, valid

labels improved the detection while invalid labels actually decreased

performance. As can be seen in the graphs below, these word labels affected both

the sensitivity and the speed of the detection. Also, interestingly the study

showed that the effectiveness of a particular label varied predictably as a

function of the match between the shape of the stimulus and

the shape denoted by the label.

Unlike

the previous studies, this report clearly shows that language affects the very visibility

of objects. The labels provided by language affect performance not just on

tasks requiring processing (explicit identification, categorization

or discrimination) of what we see but can actually make us see something that

did not exist before.

While

one interpretation would categorize such a perceptual bias as entirely

maladaptive from an evolutionary standpoint, the alternate possibility suggests

that such top-down fine-tuning of perception can make it more sensitive to

stimuli that are relevant to what is needed. Such a permeable perceptual

system would allow for influences outside of vision (such as language) to exert

an influence and to modify both perception and behavior; such as looking for a

lion, when someone screams lion behind you.

This

study clearly demonstrates that as was suspected by Whorf, our languages keenly

influence not just what we think but also what we see.

Linguistic

relativity - started off as an obscure theory, unsupported by facts and was

soon a relic in the textbooks. But empirical evidence from half a century later

has not just resuscitated the theory but has re-established it as a

cornerstone in the field.

It

seems now that Wittgenstein was well ahead of the rest of us when he

said, "Philosophy, is a battle against

the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language." In time

however, we should learn enough about these spells to free our minds and our

thoughts.

References:

- Corrupted memory, Nature, 14 August 2013,

A feature on Elizabeth Loftus by Moheb Costandi

- Regier,

T., & Kay, P. (2009). Language, thought, and color: Whorf was half right; Trends

in Cognitive Sciences, 13 (10), 439-446

- Gilbert

AL, Regier T, Kay P, & Ivry RB (2006). Whorf hypothesis is supported in the

right visual field but not the left. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences of the United States of America, 103 (2), 489-94

- Franklin

A, Drivonikou GV, Clifford A, Kay P, Regier T, & Davies IR (2008). Lateralization

of categorical perception of color changes with color term acquisition.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of

America, 105 (47), 18221-5

- Radiolab,

a public radio program from the WNYC did a wonderful one hour pod-cast on color

perception that you might want to listen to

- How does language shape the way we think? By

Lera Boroditsky

- Wikipedia

entry on Whorf.

- Language

can boost otherwise unseen objects into visual awareness, Gary Lupyan and Emily

J Ward, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, June 25, 2013

- Diamond, J

(2010). Science, 330 (332) The benefits of multilingualism

A more abridged version of this post was published in Nature India and here is the link for it.

Although, I like the crisper version too and appreciate the edits, I like the depth and flow of this one.